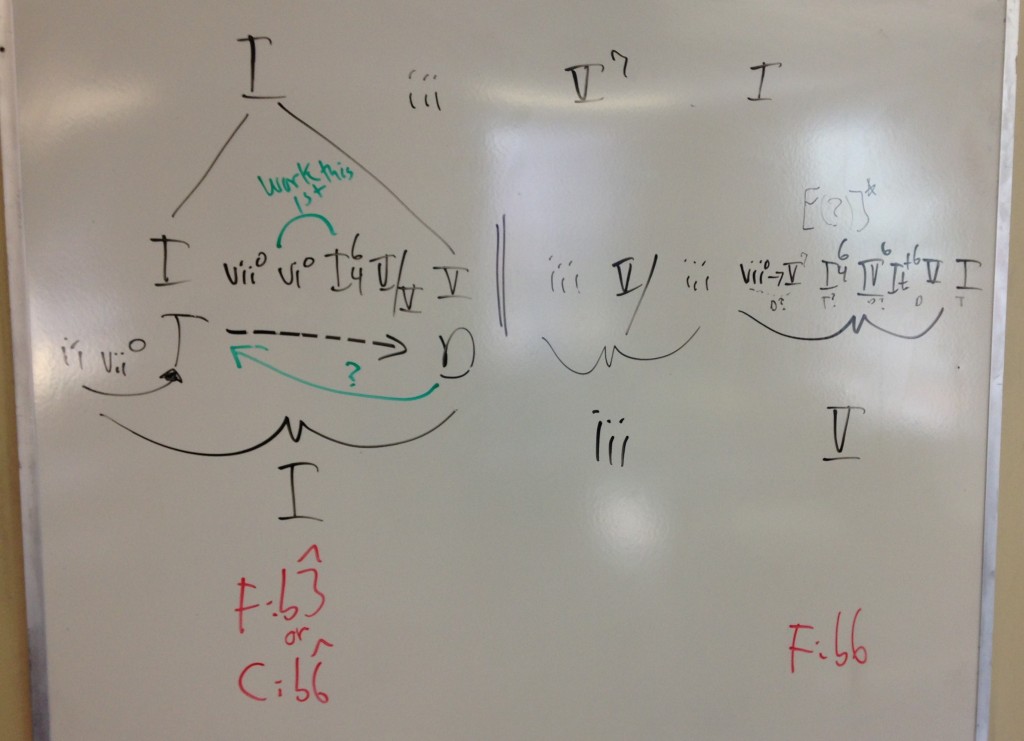

Let’s work with this template—

1) — starting with THE TONIC—how far can it be prolonged?

The black arrow typically represents contrapuntal motion towards the dominant. The repeat reminds us indeed that we do return to THE TONIC…. However, the move from V to iii is jarring, an unexpected ‘cadencing’, therefore perhaps it is not a cadencing at all!?!?!?The motion to the iii after the repeat forces the listener to re-evaluate the motion towards the Dominant—was it the arrival of THE DOMINANT, or rather an extension of THE TONIC? This is change-of-hearing is reflected by the then-added green arrow and the underlying TONIC bracket.

2) — iii is then defined and re-affirmed by its dominant

but is it THE PREDOMINANT? Here it certainly looks so…

3) — ending with THE DOMINANT—how far can it be prolonged?

Given the visual evidence (just the clarinet part!), the V bracket at the end of the charting seemed a possibility, though remote (see ?)—tonic 6/4, inverted IV chord, augmented sixth then Dominant again? It was an effort to see if we could fit in with the template suggested by Ex.101a of Felix Salzer’s Structural Hearing—see the top line.

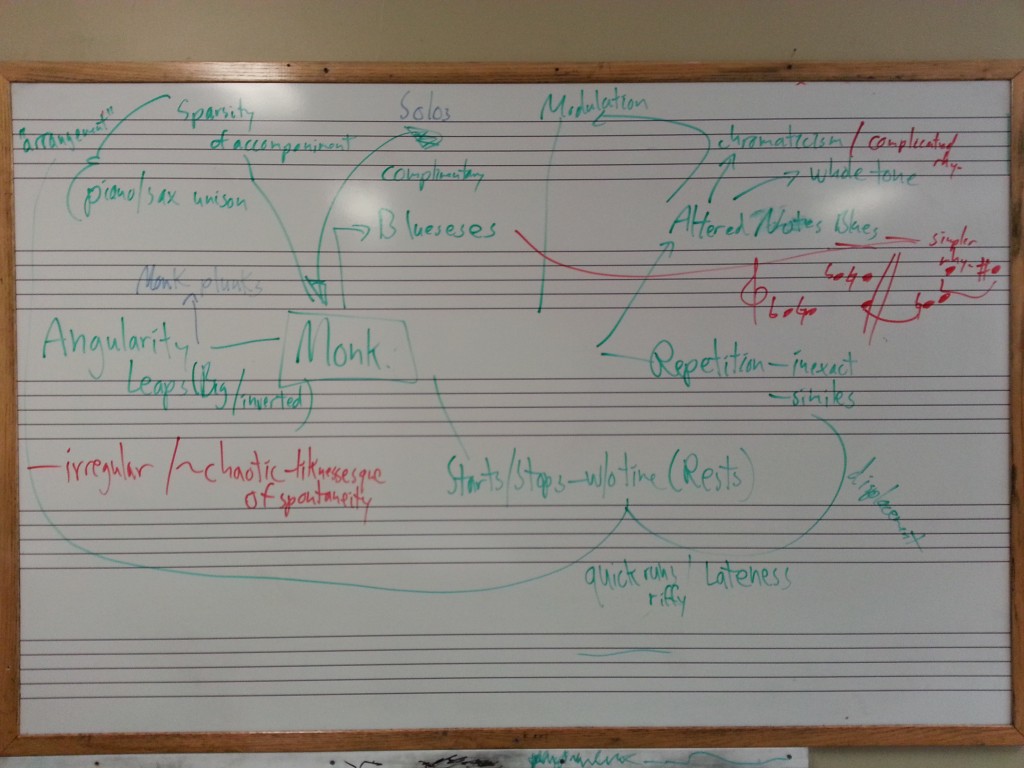

Though often regarding as simplistic, limiting, or at worst, unmusical, I find that Heinrich Schenker’s approach is quite inspiring, allowing for creativity, experimentation, even (thus this picture and this post!). Salzer’s presentation of Schenker’s approach is even more so, though it must always be kept in mind that reductive graphings can also be read in reverse as creative/additive possibilities.

BUT ALAS…!!!

After examining the score of the third movement of Brahms’ second clarinet&piano sonata, op.120, the I 6/4 after the V7 is indeed rooted (duh!). However, the iii is a predominant through that tonic-which-now-should-be-rooted. The fact that the passage continues until a more structurally progressive pre-dominant arrives in the form of a rooted IV (not inverted…) says that this is not but rather A predominant, and that 101a is not THE TEMPLATE but rather a nested prolongation to further elaborate the tonic prolongation… In other words, THE TONIC bracket should continue below the iii and continuing, essentially breaking THE DOMINANT bracket in half.

© 2014 Peter J. Evans, theorist