John Cage said “[t]he material of music is sound and silence” and that “instead of counting we use watches if we want to know where in time we are.” Cage was speaking to composers and to those interested in his sonic philosophies, but was he also speaking to improvisers?

Here is an audio recording from a free music class that captures a five-minute performance method called “11/49” whereby each improviser/performer is allowed 11 seconds of activity for each minute:

This is quite successful as a free improvisation; give-and-take, emergence of personality, drama, compelling text/non-texted sound—5 minutes just flows on by, compellingly!

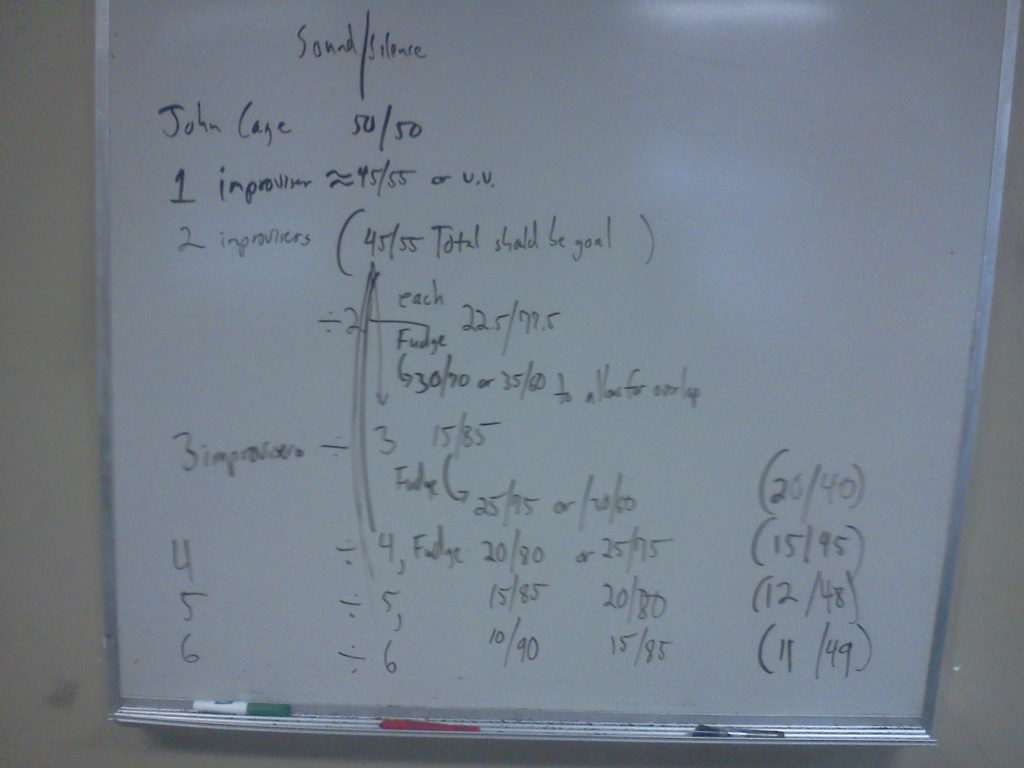

Here is a photo of the whiteboard bagatelle that lead to such results. N.B., this was devised right before, and further developing during said class: Let’s work through it a bit.

Let’s work through it a bit.

Cage balanced sound and silence as equals. For an improviser, however, I don’t think “50/50” would cut it, as it could sound like “a measure on, a measure off” or “trading fours,” etc. Therefore, I argue for skewing towards silence a bit, at a ratio of 45/55. Set a timer and equate the ratio to 27 seconds of activity to 33 seconds or inactivity per each minute. For a single improviser this makes sense, allowing ample time for the audience to recognize your “non-performative intentionality.”

If two improvisers follow the same 27s/33s ratio the audience might lose out on the sound/silence intentionality, as per minute you could have 54 seconds of activity, not nearly enough to make the point! Pure math indicates that each performer go for a 22.5/77.5 ratio, but we should skew that a bit, this time towards sound to allow for overlaps, so a ratio of 30/70 or even 35/65 would be great, the latter translating to 21sec/39sec for both performer. In total, this theoretically could result in 42 seconds of activity out of each minute, but if we actually allow/encourage overlaps AND keep in mind “silence” as a resultant aesthetic, performers could close to 50/50 or perhaps even achieve 45/55…!

The same basic process follows in the photo above for up to 5 performers. When it got to 6 improvisers (the actual number of performers in class that day), my “fudging” intentionally became even more imprecise, and the mathematical process followed throughout particular columns was “no longer relevant”. Why? The fourth column had become a simple arithmetic progression, by 5, while the fifth column was likewise proceeding by 3 for each iteration, and the idea of continuing in this manner seemed a little too “harmonious” perhaps, so I just changed it to what I thought was a more fitting amount. PLUS, 11:49 had an intriguing ring to it…

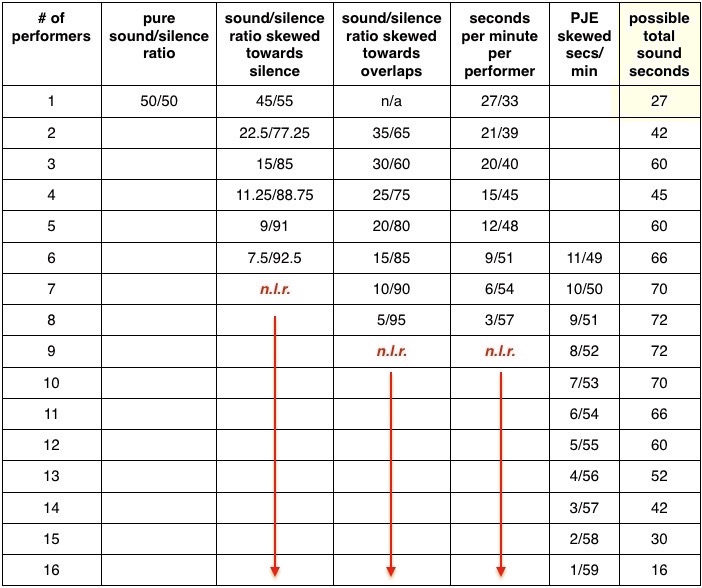

Here’s a chart that lays out the above information and carries through to 16 performers: The last column provides a maximum amount of sound possible, just for the sake of information for the ensemble leader—for one, two, fourteen or fifteen performers, let things fly, but aesthetic “Silence should be (at least) half of the Sounds” will need to be taught and enforced for all other group sizes.

The last column provides a maximum amount of sound possible, just for the sake of information for the ensemble leader—for one, two, fourteen or fifteen performers, let things fly, but aesthetic “Silence should be (at least) half of the Sounds” will need to be taught and enforced for all other group sizes.

The chart would seem to suggest that a group of 15 improvisers would be quite interesting, yet 16 would take a lot of practice to get the feel of things right. Any more people, and you could perhaps multiply the values of the sixth column by additional minutes, or split everyone into different groups of 15 which alternate minute-by-minute.

N.B. Of course, any number of performers who improvise by highlighting distinctions in timbre and/or melodic angularity and disjuncture will make themselves stand apart, regardless of style, texture and size of ensemble, and even more so in this case—in fact, when such persons are “silent” it becomes quite obvious by occlusion!

© 2018 Peter J. Evans, theorist